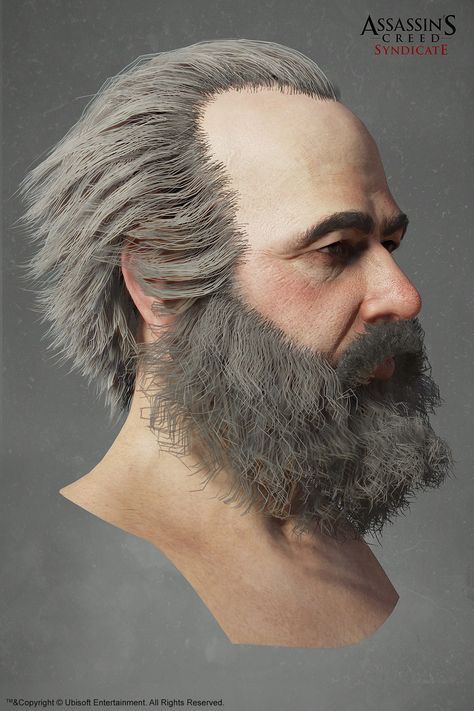

Memory 01 — Cat and Mouse — Karl Marx — London Stories | Assassin’s Creed: Syndicate

Guide Info

Favorite

Choose from over 100 Games at the Ubisoft Store!

| Optional Objective/s |

|---|

| 1. Kill spies with hanging barrels (2 spies). |

| 2. Create a faction fight outside the pub to attract the spy. |

Subscribe to Premium to Remove Ads

| Reward/s | . | . | . |

|---|---|---|---|

| Money: | 800 £ | 125 £ | |

| XP: | 700 XP | Bonus: | 150 XP |

| Gear: | N/A. |

Part 1: Escort the Ally¶

Once the gameplay portion of the memory begins, follow Marx out of the train station. He’ll lead you through an alleyway marked as a restricted area with a green search zone placed over the top.

Subscribe to Premium to Remove Ads

As he moves through the alleyway, a series of spies will approach our ally and we’ll need to kill them before they reach him – you’ll need to switch on your Eagle Vision to identify them (there are 4 in total and you should do this right away). The unfortunate part of this is that there is also a fairly heavy police presence and any hostile actions will cause them to become hostile.

The unfortunate part of this is that there is also a fairly heavy police presence and any hostile actions will cause them to become hostile.

During this escort sequence, we can earn the first optional objective – to kill two different spies using hanging barrels.

Subscribe to Premium to Remove Ads

To earn the optional objective, you’ll want to wait for our buddy to walk into and through an area with a spy. Allow a spy to follow him a short distance until said spy is located below a set of hanging barrels. Bring them down on him. There are three sets of hanging barrels along this escort route and four spies – so plenty of opportunity!

View Full-size

Follow Marx out of the train station (left). As you follow him down the alley, use the hanging barrels (right) to defeat the spies.

Subscribe to Premium to Remove Ads

This entire escort segment is made much easier by using the Rope Launcher to reach the rooftops and following the friendly from above. This also allows you to target the hanging barrels without triggering the police to attack and also seeing their area of effect so that you can hit the spies with greater degree of accuracy.

This also allows you to target the hanging barrels without triggering the police to attack and also seeing their area of effect so that you can hit the spies with greater degree of accuracy.

Eventually our escort will leave the alley and cross the street into an outdoor storage area of sorts. Here you’ll need to fight off any police you may have incidentally annoyed during the escort.

Subscribe to Premium to Remove Ads

Part 2: Gang Fight¶

When our ally is ready to move on, he’ll lead us back to the street and tell us to deal with a spy in a pub up the road.

We can earn the second optional objective at this point. To do so, we’ll need to start a gang fight to draw the spy out.

Subscribe to Premium to Remove Ads

Outside of the entrance to the pub, you’ll see a group of Blighters and a group of Rooks conveniently located on opposing sides of the street. Recruit the Rooks and have them attack the Blighters. This will trigger a small-scale gang fight.

View Full-size

Locate the Spy in the pub (left). Hire some Rooks and have them attack some Blighters (right) to draw the Spy outside.

Subscribe to Premium to Remove Ads

During this fight the policemen and spy located inside the pub will come out to join in the fray. Take this opportunity to kill the spy to complete the optional objective.

Once the street is clear of hostiles, follow Marx into the pub and then another short distance through some back alleys until another scene plays.

Subscribe to Premium to Remove Ads

Part 3: Kidnap the Spy¶

After the short cut-scene we’ll need to kidnap the target who is flanked by four policemen – tricky! The easiest way to do this is to tail the group until they reach the streets at which point they will all hop into a number of carriages.

Follow the target carriage a short distance until there are not as many police around before hopping onto the roof and hijacking the target vehicle. This should force the target onto the street. Climb out of the carriage, move up and kidnap him. Stick him into the back of the carriage.

Climb out of the carriage, move up and kidnap him. Stick him into the back of the carriage.

Subscribe to Premium to Remove Ads

Drive to the destination and deliver the target to the nearby objective marker for a scene to end the memory.

What the New Assassin’s Creed Gets Wrong (and Right), According to a Historian

By

Chris Suellentrop

Comments (253)

We may earn a commission from links on this page.

Bob Whitaker, a historian of modern Britain at Louisiana Tech and the host of the YouTube series History Respawned, recommends Assassin’s Creed Syndicate, the entertaining new Ubisoft game set in Victorian London. He likes the way it successfully captures the feel of the British capital in the 19th century, and he particularly likes the way the game depicts the Thames River as crowded with industrial traffic. But he still has some nits to pick.

But he still has some nits to pick.

Whitaker fact-checked the game from a historian’s perspective during an interview I conducted for my podcast, Shall We Play a Game?. You can listen to the podcast here. The excerpts below have been condensed and edited.

Minor spoilers for Assassin’s Creed Syndicate follow.

The Game Overstates the Class Struggle in London

“They decided to set the game in 1868,” Whitaker said. “This is the high point for the Victorian era. This is Britain coming into its own, dominating industrial production, particularly steel production and textile manufacturing. And also it’s beginning to dominate financial capitalism through the world.

“This economic prosperity has led to a better quality of life for not just the wealthy in Britain but also the lower classes. Between 1850 and 1870, the average pay for an industrial worker doubled in Britain. In this game, Ubisoft has depicted it as an era of class struggle, but really by 1868, a lot of the heavy class struggle, the sharp divisions between the classes based on economics, has actually subsided in Britain.

“In particular, in 1867, the year before this game is set, the Parliament had passed the Second Great Reform Act, which effectively expanded, or doubled, the franchise in Britain—allowing industrial laborers to vote in parliamentary elections for the first time. So Ubisoft wants to paint this as an era of Dickensian, Marxist class struggle, but at this point in 1868, a lot of that class struggle, a lot of that Dickensian nature, has actually subsided.

“In fact, Karl Marx critiqued the industrial workers of Britain, saying that they had gotten too used to economic prosperity, and he began to refer to them as ‘the bourgeois proletariat.’”

As the Game Suggests, Karl Marx Was a Social Democrat in 1868

“The thing about Marx is that, by the late 1860s, he is somebody who is encouraging workers to unite into parties and to actually engage with parliamentary democracy. And this pits him against the rising group of anarchists, both within Britain and also within continental Europe, who feel that the workers will never be able to achieve their goals unless they completely destroy the political system.

“So I actually think the depiction of Marx in this game is pretty accurate, simply because they’re showing this division between his followers and his theories compared with the anarchists, who are shown in this game with one British person hoping to blow up Parliament who ends up killing himself.”

London Needs Prostitutes, But Not for the Reasons You Think

“I know a number of reviews, including one by the feminist critic Anita Sarkeesian, lauded this game for the removal of the prostitutes on the streets. But the thing is, Victorian society was obsessed with prostitution, was obsessed with this idea of ‘fallen women.’ This was a particular point of emphasis for famous Victorians like William Gladstone and Charles Dickens. Charles Dickens, in fact, helped to run a house for fallen women to try to rehabilitate them.

“I can understand why people are happy that the prostitutes are removed from Assassin’s Creed, but it seemed like it would have been a great opportunity to highlight a really important moment in the history of feminism. A lot of historians, people like Judith Walkowitz and others, argue that the campaign against prostitution, against fallen women, gave rise to modern British feminism. And in particular, the campaign of British feminists against the Contagious Diseases Acts, which emerged in the 1860s.

A lot of historians, people like Judith Walkowitz and others, argue that the campaign against prostitution, against fallen women, gave rise to modern British feminism. And in particular, the campaign of British feminists against the Contagious Diseases Acts, which emerged in the 1860s.

“These Diseases Acts were designed to imprison women who were suspected of carrying venereal diseases. They also subjected potential prostitutes to examination by police. This series of acts during the 1860s led to a campaign, which saw not only working class women but also upper class British women working together to combat these illegal examinations, to combat the imprisonment of women by the authorities, and eventually saw one of the first big successes in feminism during the 19th century.

“In particular, since you’ve got Evie there, you could see her helping one of the main feminists, somebody like Josephine Butler, attempt to save prostitutes from illegal imprisonment by the police. I think that would make for a great mission. ”

”

The Assassins Should Support Gladstone Over Disraeli

“Later on in the game, about three quarters of the way through, you meet Benjamin Disraeli and William Gladstone. These two are the main political rivals of 19th century British politics. What’s interesting is Ubisoft has you and the Assassins fighting alongside Benjamin Disraeli, which is very odd because Disraeli was the conservative politician facing off against William Gladstone, the liberal politician. It’s true that Disraeli was known for being more supportive of workers, which would fit in more in line with the Assassins’ mission in the game. But at the same time, Disraeli was also a huge promoter of tradition, of traditional values, of hierarchy in society. Furthermore, he was a huge supporter of imperialism, which seems very antithetical to the Assassins and their creed. Whereas Gladstone was a huge promoter and creator of major reforms during his time in British politics.”

The Assassins May Be Campaigning Against Legal Child Labor

“There’s a depiction in this game of child labor. This is pulled straight out of Dickens, but I think the child labor shown in this game is much more accurate for the 1840s and 1850s. By the 1860s, the late 1860s in particular, child labor was pretty well regulated.

This is pulled straight out of Dickens, but I think the child labor shown in this game is much more accurate for the 1840s and 1850s. By the 1860s, the late 1860s in particular, child labor was pretty well regulated.

“In fact, I’m not exactly sure that the child labor mills depicted in this game were illegal according to Victorian law. In the 1860s, they passed a number of laws saying that children over the age of 8 were allowed to work in factories as long as they would only work for eight hours. I can’t be certain how old the children are in Assassin’s Creed Syndicate, but if they’re over 8 years old, those factories that the Templars are running are perfectly legal.”

London Was Not That White

“There’s not much reference to the British Empire in this game. There is one Assassin character named Henry Greene, who is from India. There is also the Sikh maharajah depicted in this game, briefly. But other than that, there really isn’t any other person or storyline that deals with the British Empire.

“So that was surprising, particularly as this game is set in the late 1860s. You’ve got the rise of Irish nationalism, and in particular you have the development of the Irish Fenians, who were a group of Irish nationalists who began to plot the assassination of British officials and also began to plant dynamite bombs in various government offices.”

“I’m not saying that you should have side missions taking place in India, or side missions taking place in Canada. Not necessarily going to the Empire, but at least depicting a version of Victorian London that includes the empire, and includes imperial citizens—people from Africa, people from the West Indies, people from Australia, more people from India.

“At this time, London would have included a whole host of people of color throughout the street. Even in addition to the empire, Britain was a major international trading center. So you wouldn’t have just had British citizens, British subjects, there. You would have had people of color from all across the world. ”

”

Subscribe to Shall We Play a Game? on iTunes, Android, or the podcast app of your choice. You can also follow the podcast on Twitter or like it on Facebook.

Chris Suellentrop is the critic at large for Kotaku and a host of the podcast Shall We Play a Game? Contact him by writing [email protected] or find him on Twitter at @suellentrop.

What is Karl Marx to blame for

Planned indicators could easily be exceeded by increasing costs / Rudolf Alfimov / RIA Novosti

Few people know that Paul Samuelson’s classic textbook «Economics», at that time one of the best publications in the world describing the theory market economy, was first published in the USSR in 1964. That is, 50 years ago, during the heyday of planned production, Soviet economists had the opportunity to get acquainted with the then advanced economic science. Of course, one book does not make a difference, but in fact foreign economic literature was published quite regularly in the Soviet Union. At 1960s–1970s even a whole series of «Library of Foreign Books for Economists and Statisticians» was published. Let’s add here an excellent mathematical school and computerization, which was rapidly gaining momentum, combined with the mandatory nature of collecting statistical information.

That is, 50 years ago, during the heyday of planned production, Soviet economists had the opportunity to get acquainted with the then advanced economic science. Of course, one book does not make a difference, but in fact foreign economic literature was published quite regularly in the Soviet Union. At 1960s–1970s even a whole series of «Library of Foreign Books for Economists and Statisticians» was published. Let’s add here an excellent mathematical school and computerization, which was rapidly gaining momentum, combined with the mandatory nature of collecting statistical information.

Why, then, were all these seemingly obvious advantages not realized in the flow of new products, in the growth of consumption and prosperity? The apologists of socialism and its opponents together cite many reasons that led the Soviet economy to collapse. Here and the arms race, and the «betrayal» of the corrupted elite, and illiterate attempts at reform. To list such reasons and analyze their advantages and disadvantages is a thankless and meaningless work, since most of the disputants are likely to be completely sure that they are right. Even Max Planck noted: “A great scientific idea is rarely implemented by gradually persuading and converting its opponents. In reality, what happens is that the opponents gradually die out, and the growing generation gets used to the new idea from the very beginning. So, without trying to look for arguments in a useless dispute, let’s try to understand what the Soviet economy lacked. nine0003

Even Max Planck noted: “A great scientific idea is rarely implemented by gradually persuading and converting its opponents. In reality, what happens is that the opponents gradually die out, and the growing generation gets used to the new idea from the very beginning. So, without trying to look for arguments in a useless dispute, let’s try to understand what the Soviet economy lacked. nine0003

Undoubtedly, at its best, the Soviet Union, if not in the leading positions in the world, was at least close to them. At the same time, next to the fantastic achievements in Soviet enterprises, one could easily meet the technologies of the 19th century. How to explain this phenomenon? Why didn’t the much-lauded diffusion of innovations take place? Where did the multiple developments of Soviet scientists disappear? Who prevented the introduction of new technologies and forced them to work on antediluvian equipment for decades? nine0003

Despite the large number of subjective reasons that arose in each specific case, there were errors in the system as a whole, which limited the possibilities of development and stood in the way of numerous sprouts of efficiency. And the main systemic mistake of the Soviet economy was Marxism. However, it is more correct to speak here of Marxism in its narrow sense, as a comprehensive economic theory.

And the main systemic mistake of the Soviet economy was Marxism. However, it is more correct to speak here of Marxism in its narrow sense, as a comprehensive economic theory.

It is not worth now to retell in full the economic views of Marx, which in themselves were very curious and served as an impetus for the development of many modern economic trends. For us, those individual propositions of Marxism will be important, which became a stake in the Soviet economy and up to 1990s didn’t let her develop.

And the first among the Marxist economic delusions is, perhaps, the concept of constant capital, which, apart from Marx, is not used by anyone else. In an effort to justify the labor theory of value, Marx was forced to construct the term «constant capital», investing in it the cost of acquiring equipment, raw materials and supplies, but without the cost of labor, the costs of which he called «variable capital». Having come up with such a construction, Marx came to the conclusion that labor productivity can be measured through the ratio of variable and constant capital. The smaller it is, the better. Let’s consider a simple example. The worker on the machine makes bolts. The less time he spends on making one bolt, the more efficient it will be. Well, as a measure of output, Marx proposed the concept of «total social product.» nine0003

The smaller it is, the better. Let’s consider a simple example. The worker on the machine makes bolts. The less time he spends on making one bolt, the more efficient it will be. Well, as a measure of output, Marx proposed the concept of «total social product.» nine0003

Soviet economists, taking literally Lenin’s phrase “Marx’s teaching is omnipotent because it is true”, put the total social product at the forefront of the Soviet economy, understanding by it the total cost of goods and services produced and including there, in full accordance with Marx, the costs for raw materials and supplies. And it was this inclusion in the cost of the cost of raw materials and materials that was their main mistake.

Imagine a hierarchy of plans built according to Marxist doctrine. The plan of any plant is a piece of the planned total social product. And, of course, it is considered in two forms — natural and cost, and the cost will, of course, be preferable. But what happens if the company starts to reduce the share of costs? In a system where costs increase the cost of the final product, the implementation of the government plan becomes more and more difficult. Conversely, an increase in costs will allow you to exceed the planned targets without much effort. nine0003

Conversely, an increase in costs will allow you to exceed the planned targets without much effort. nine0003

Of course, if the state continuously tries to reduce costs through administrative measures, it will be able to do something. You can finally set the plan in natural units. But in this case, the company simply starts producing new, slightly modified products, which will be more expensive.

Let’s go back to our bolt example. If you set the plan in money, then you can make the bolt a little more expensive by changing the material, say, titanium instead of steel, increasing costs and, consequently, the price. It’s easier than letting out more bolts. If the plan is in pieces, you can develop new bolts that are more expensive than the old ones, name them differently and again exceed the plan in terms of money. nine0003

Bolts is a hypothetical case, but here is a real example. In the 1980s the scarce washing machine «Vyatka-avtomat» was supplied with a cast-iron weighting agent, while its foreign counterparts used cheaper and more technologically advanced concrete for this purpose. Naturally, there were no difficulties for Soviet engineers in replacing cast iron with concrete, however, as well as reasons to do this.

Naturally, there were no difficulties for Soviet engineers in replacing cast iron with concrete, however, as well as reasons to do this.

Of course, newly created enterprises will be more efficient, so that the economy as a whole will show an increase in productivity. However, not a single old enterprise will be able to significantly improve its economic performance. Except on paper. Real cost reduction will not benefit either management or workers. nine0003

Interestingly, in the 1970s, after the Soviet mathematician Leonid Vitalyevich Kantorovich was awarded the only Nobel Prize in Economics for the USSR “for his contribution to the theory of optimal resource allocation”, Soviet leaders tried to introduce optimization methods at a number of enterprises, but quickly abandoned This, because optimal solutions sharply reduced the possibility of fulfilling a plan drawn up in gross terms and linked to the total social product. And it was impossible to introduce indicators based on the calculation of profit without changing the Marxist system of a planned economy. nine0003

nine0003

But this is only the first difficulty left by Marx. According to the then economic views, Marx believed that the total social product is created only in the sphere of material production. But the non-productive sphere, according to Marx, does not create a total social product. And if so, then there is no need to develop it.

In full accordance with the letter and spirit of orthodox Marxism, the Soviet leaders did their best to develop the sphere of material production. The trouble is that Marxism attributed state administration, culture, as well as household and medical services to the non-productive sphere. The Soviet Union, of course, developed them in a planned manner, but did it solely on a residual basis. Well, since the state never had enough money, the development of the non-material sphere lagged far behind the needs of the population. nine0003

At the same time, the Western economy built its economic priorities according to other canons. Let’s start with the fact that the main economic indicator in the world was the gross national product (GDP), free from the shortcomings that the Marxist total social product had. Firstly, the GDP did not include intermediate consumption, in which all costs were concentrated, and secondly, the service sector was absolutely equal in it with the manufacturing industries.

Firstly, the GDP did not include intermediate consumption, in which all costs were concentrated, and secondly, the service sector was absolutely equal in it with the manufacturing industries.

From 1960s The service sector in the world grew at a faster pace, spurring economic growth. In the modern post-industrial world, the share of services is more than 60% of GDP. Only now the Soviet economy did not receive this significant addition. On the contrary, seeing its lagging behind, the country’s leadership began to further reduce the costs of the service sector in favor of the development of production, forcing the regions to resort to tricks and even outright forgery. In the 1980s The author of these lines had a chance to see in the cities of the Komi ASSR the construction of palaces of culture, which are extremely necessary for the republic, passing according to official documents as “houses of technology”, since there was no money for culture in the budget. nine0003

Soviet engineers and scientists struggled to introduce new, more advanced methods of production, but this ran into the full power of socialist planning, and funding for science did not provide scientists with material incentives. And if fundamental science could still be developed in this way, then applied scientists, whose results should, in theory, lead to an increase in economic efficiency, could not earn money on the introduction of new technologies and received crumbs that rather discouraged them than pushed them to new ones. discoveries. nine0003

And if fundamental science could still be developed in this way, then applied scientists, whose results should, in theory, lead to an increase in economic efficiency, could not earn money on the introduction of new technologies and received crumbs that rather discouraged them than pushed them to new ones. discoveries. nine0003

The result of this is well known. The Soviet economy could not stand the competition with the market systems of the capitalist countries. Is Karl Marx to blame? Hardly. Rather, its primitive interpretation is to blame, which turned an outdated economic theory into a dogma of real economic management of a large country. Everything else, including the impossibility of planning such a complex system, was already a consequence. Alas, the plan cannot be reconciled with profit and competition, and competition itself means economic freedom incompatible with socialist principles. And I really want to believe that the time of socialist experiments is still in the past for Russia.